The role of CAT tools in Patent Translation

Tesi di laurea in Laboratorio CAT

Serena CUSCIANNA

UniversitĂ del Salento, A.A. 2018/2019

1. THE PATENT: OVERVIEW

A patent is a legal document that grants authority and specific rights to the inventor. Over the years, each government has developed an accurate patent law to exactly define what is patentable, which elements must be part of a patent, and which steps must be taken to obtain and defend Intellectual Property (from now on, IP). These points will be discussed in more detail in the following sections along with a presentation of the main actors involved in the patent process.

1.1 Definition and patentability requirements

A patent gives exclusive rights granted by a sovereign State to an inventor or assignee for a limited period in exchange for detailed public disclosure of an invention. The protection of IP through patents prevents third parties from producing, selling, exporting or using the invention without authorization (Durton, 2018, p. 7). Thus, it is a form of IP right that should not be confused with other types of rights, such as copyrights, servicemarks, and trademarks. If the origin of the word is considered, it is not clear what the etymology of the word “patent” is. In fact, according to Perotto (2008, p. 17), the term “patent” corresponds to the abbreviation of the English literal translation of the Latin expression “litterae patentes” (in English, “letters patent”). Letters patent were the official documents which conferred and made public certain privileges, rights, and titles. On the other hand, according to Durton (2018, p. 7) «the word patent is derived from the Latin word “patere” which means to disclose, lay open, to expose, to make accessible, etc.». However, Durton points out that the term and its use have evolved before arriving at its modern use.

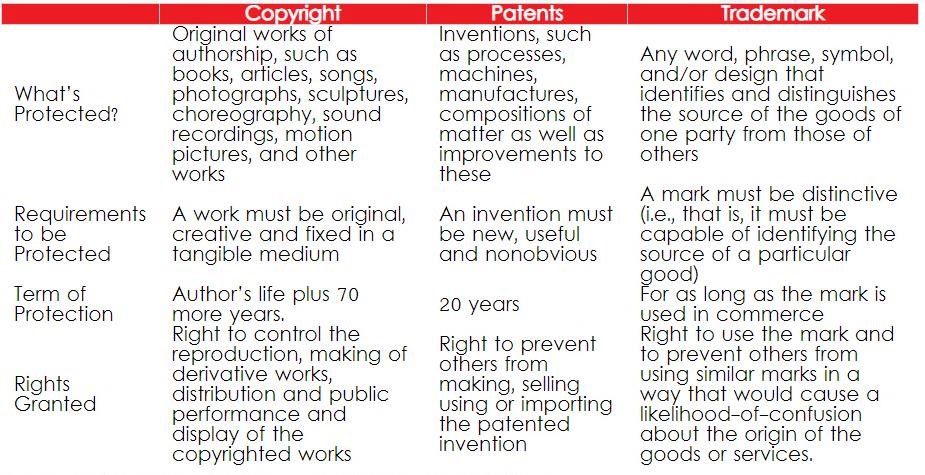

As mentioned above, when it comes to intellectual property, reference is made to a broad and varied concept. In order to benefit from the intended rights, inventors and owners of intellectual properties must know the difference between a patent, copyright, trademark, and servicemark. Although these terms are often used as synonyms, they each offer a different degree of protection. Trademark and servicemark are the concepts with the highest degree of affinity. In fact, «the major difference between the two is that while the former identifies the owner of a product and differentiates it from other similar products on the market, the latter identifies and differentiates an originator of a service from others» (Durton, 2018, p. 23).

In summary, to sell a product a trademark is needed, while a servicemark is necessary to offer a service. This kind of right may secure logos, names, slogans, symbols, phrases, among other things, with unlimited protection’s terms, because «it is the usage that bestows the right on the owner» (Durton, 2018, p. 23). As for copyright, Durton (2018, p. 24) gives the following definition:

Copyright is another type of right […] given to the author of original works such as musicals, artistic, dramatic and literary works such as novels, poetry, architecture, computer software, songs, and movies. Like a patent and unlike trademark/servicemark, the right is not an everlasting right. But its duration is more complex than that of a patent as a number of factors are taken into consideration to determine it.

The figure below summarizes the main differences between copyright, trademark, and patents (Retrieved from https://copyrightalliance.org/ca_faq_post/difference-copyright-patent-trademark/).

Patenting an idea is paramount for several reasons. Firstly, it is crucial for the development of the art, by encouraging all competitors, who cannot copy an invention, to search for new patentable techniques. Moreover, many entrepreneurs decide to enhance the image of their company and improve their market position through patents. Finally, the patent guarantees additional profits. The owner can either sell the patent by transferring his rights to the new owner or grant a license allowing another person to use the patented invention for a fee.

A lot of things, ranging from concrete items to processes and chemical formulas, can be patented. Although each State or international organization has approved its own patent legislation, it is possible to identify three generally shared patentability requirements: novelty, originality (inventive step) and industrial applicability. For the sake of simplicity, the following definitions have been extracted from the European Patent Convention (As amended on 01.04.2019 since the publication of the 16th edition (June 2016) of the Convention on the Grant of European Patents as in force since 5 October 1973), as both Italy and the United Kingdom have signed it.

According to the Article no. 52 clause 1, «an invention shall be considered to be new if it does not form part of the state of the art». In other words, at the time of filing the patent application, the invention must not have been previously disclosed or made available to the public (Perotto, 2008, p. 23).

According to the Article no. 56, «an invention shall be considered as involving an inventive step if, having regard to the state of the art, it is not obvious to a person skilled in the art». Hence, an invention should be neither obvious nor trivial. On the contrary, it should be characterized by originality.

According to the Article no. 57, «an invention shall be considered as susceptible of industrial application if it can be made or used in any kind of industry, including agriculture».

Therefore, not every article or idea is patentable. For example, scientific theories and mathematical methods, aesthetic creations, rules and methods for doing business and programs for computers, cannot be considered patentable. It is important to seek advice from a patent attorney if there are concerns about whether an idea is patentable. As soon as the inventor has insured that the invention meets all the criteria for patentability, he/she must choose the type of patent that best suits his/her needs. The main typologies of patents will be analyzed in detail later on.

1.2 Typical structure

While patent law varies according to national laws and international agreements and, therefore, it deserves to be discussed in a separate section of this dissertation (see chap. 1.5), the internal organization of a patent is quite invariable. Some elements are mandatory, such as one or more claims, the cover page, or the specification, while others are optional, such as the drawings.

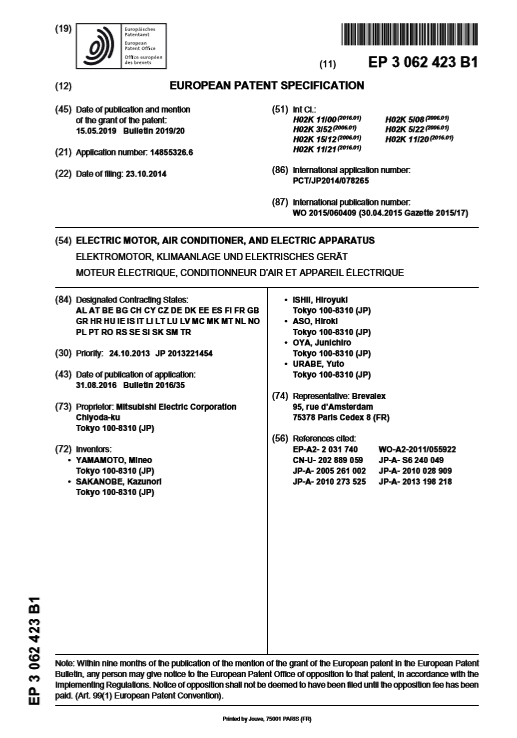

The bibliographic information reported on the cover page (FIG. 2) marks the beginning of a patent. As stated by Zerling (2009, p. 1), «for those translators who are unfamiliar with patents, the cover may appear to be confusing and difficult to translate».

The front page contains important useful data for searching and examining patent applications, such as the title of the invention, the date of filing, the application number, the publication number, the date of publication of the application, the priority, the names of patentees, inventors, and representatives, etc. Each item is preceded by a code number in parenthesis, known as INID (Internationally Agreed Numbers for the Identification of Data) code. As Hartmann explains, «this code allows the critical data in the patent to be extracted regardless of the languages used on the cover page» (Hartmann, 2007, p. 12).

The description of the invention corresponds to its detailed explanation. It must be written so that an expert in the art may reproduce the invention after the expiry of the patent. No fixed structure and sequence of elements in the description exist. However, according to Zerling (2010, p. 1), it has to include information about:

- the technical field to which the invention belongs;

- the background, or the prior art;

- the problem the invention intends to solve, including the shortcomings or disadvantages of the prior art;

- the solution proposed to solve the mentioned problem, including the advantages it offers;

- a description of the drawings, if any, including the direction of view and relationship with other figures;

- the description of at least one preferred embodiment, with reference to the drawings, if any, in order to explain how to make and use the invention;

- the claims;

- the abstract.

The drawings represent the non-linguistic, or paralinguistic, elements of the text. The drawings are not mandatory, since in some cases (e.g., chemical or process-related patents) they can be omitted. In all other cases, «they may include drawings of a physical object, views of a graphical user interface, electrical diagrams, flow charts, and many other graphics that can be used to explain an invention» (Patent Basics – Parts of a Patent Application – https://turbopatent.com/parts-of-a-patent/).

The claims need the highest degree of attention. It is extremely important to have well-crafted patent claims since they are legal documents to protect the invention and to prevent others from exploiting the invention. The claims are the only part of the patent that is enforceable, hence it is of crucial importance to properly draft them. According to the Patent Corporation Treaty (PCT), «an appropriate claim is one which is not so broad that it goes beyond the invention nor yet so narrow as to deprive the applicant of a just reward for the disclosure of the invention» (WIPO, as of July 1, 2019).

There are three types of claims:

- the independent claim, which corresponds to the first claim and contains the essential features of the invention. More than one independent claim may also exist if the patent has more than one object;

- the dependent claim (i.e., one or more claims that depend on the main claim), of which all limitations are included;

- the multiple dependent claim (i.e., the one depending on more than one claim).

As Hartmann (2007, pp. 13-14) clearly explains:

claims usually have a two-part structure. The first part is the preamble […], which designates the subject matter in terms of the prior art that is relevant to the invention. […] The second part is the characterizing clause or characterizing portion. […] This part describes the aspects of the invention that are novel and inventive […] and therefore should be protected.

Lastly, the patent document may also include a concise summary, generally in the cover page, with the sole purpose of briefly indicating technical information.

1.3 Main typologies

Depending on the legislation in force, each State may be able to grant different typologies of patents. The most common form of patent, and often the only possible one, is the patent for invention, also known as a utility patent. A utility patent should not be confused with a utility model patent. The patent for invention is intended to protect an invention having technical characteristics (i.e., representing the structural or functional solution of a technical problem). For example, it may concern a device or a method for its operation (Perotto, 2008, p. 33). As a general rule, the invention should be operable or usable, of practical use, and beneficial. The patent for invention guarantees protection for 20 years. During this period, the invention may not be used, sold or exported without the permission of the patent holder. Furthermore, legal action for infringement may be filed, if necessary, or compensation may be claimed for any illegal use of the product protected by the patent (Durton, 2018, p. 11). The process of the application of utility patents will be discussed later on.

As already noted, it is important not to confuse utility patents with utility model patents. In fact, the latter is used in some Countries to protect the so-called “minor inventions” (i.e., improvements or modifications to existing inventions or technical innovations which might not qualify for a patent). The distinction between a patent for invention and a utility model patent is not based on differences at the inventive step, but objective characteristics. On the website of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the main differences are summarized as follows:

In general, compared with patents, utility model systems require compliance with less stringent requirements (for example, lower level of inventive step), have simpler procedures and offer shorter terms of protection (10 years, Ed.). Designed primarily to respond to the needs of local innovators, requirements and procedures for obtaining protection and the duration of protection vary from one country to another.

To classify the content of patents and utility models more rigorously, and to simplify the retrieval of patent documents when searching for “prior art”, an international hierarchical system has been established by the Strasbourg Agreement 1971: the International Patent Classification (IPC). The IPC divides inventions into eight categories (human necessities, performing operations/transporting, chemistry / metallurgy, textiles / paper, fixed constructions, mechanical engineering / lighting / heating / weapons / blasting, physics, electricity), each one marked with a letter (from A to H). Furthermore, each category is divided into subdivisions (and related symbols) in order to provide more details on the content.

Besides the two typologies of patents mentioned above, it is also possible to opt for other types of rights, which do not always fall within the “patent” category. For example, according to the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), «a design patent is a type of patent issued to creators of unique visual elements of manufactured products» (Durton, 2018, p. 12). In the UK, however, patents only apply to inventions. Designs are protected through unregistered design rights or registered designs. Likewise for the patenting of new plant varieties. A plant patent is one of the kinds of patents issued in the US, but it may not be obtainable in some other Countries. For example, under the European Patent Convention (EPC), to which most European Countries are contracting States, plant varieties are excluded from patentability. However, the UK and Italy have separate rights for plant breeders.

1.4 Typical lifecycle of a patent

The application and grant procedure for a patent is a long and complex one and may require expert handling as well as adequate financial means. For this reason, before undertaking the patenting process, it is important to assess risks and benefits, potential economic profits on the market and whether the patent is the most appropriate type of right to be exploited. Before deciding to patent, an inventor must consider some general issues, as indicated on the European Patent Office (EPO) website. Some questions are shown below as an example:

Do you really need a patent? Would some combination of other forms of IPR protect your idea adequately? […] Have you studied the total cost of patenting (which should include annual renewal fees in every country in which you have protection)? […] Is the time right to apply for a patent? […] Who will pay to enforce your patent? […] How strongly might your patent resist a legal challenge?

If one decides to proceed with the patent application, it is helpful to know that the typical lifecycle of a patent may vary depending on the patent office in charge although they generally tend to follow a common pattern. Typically, the first step is to research the existing state of the art. Millions of patents are granted in the world every year, so if proper research is not carried out, there is a high probability that, due to a lack of patentability requirements, the invention or certain aspects of it will not be recognized as patentable.

The next stage is the drafting and submission of the patent application. The application must include a description of the invention which allows others to see how it works and how it could be made, the claims on which the scope and purpose of the patent are based, the drawings if needed, and an abstract for technical purposes.

The government agency responsible for intellectual property rights will examine the application in order to check whether all the necessary information and documentation has been provided and whether the application fee has been duly paid. This verification process is called “formalities examination”. If the documentation appears correct, a filing date, also known as the priority date, is given to the application. The filing date may be of paramount importance, in some Countries more than others. The priority of an application over any other applications for the same or similar invention may be established by determining the date of filing (first- to-file principle, applicable in Europe), or the date of invention (first-to- invent principle, applicable in the USA).

As part of the application process, the applicant must pay for a patent search: in parallel with the formal examinations, a search is carried out to check whether the invention is new and inventive and whether description and claims match and are good enough to patent. In case of a positive response, a search report is sent to the applicant in order to facilitate an instrument to counter any objection raised during the examination. At this point, the applicant has the last opportunity to decide whether to continue or withdraw the application (the deadline is indicated in the search report).

The application is published 18 months after the filing date. From that moment on, the invention will appear in databases and will act as prior art against any future patent application. At this point, the applicant has six further months to decide whether to request a “substantive examination” and, thus, continue with the application and which Countries should be included in the patent protection. A patent application, in order to be filed at the European level, must have a version of the description written in a language of choice between English, French, and German. On the other hand, claims must be published in all three languages.

Afterward, translated versions in each language will be required to obtain protection in each Country (Perotto, 2008, p. 37). Although translation costs account for about 25% of the total, it has recently been shown that translations are only consulted in extremely rare cases (Perotto, 2008, p. 38). If a “substantive examination” is requested, the examiners, in the light of the search report and taking into account the applicant’s reply to the report, will ensure that both invention and application meet the related requirements. At the end of this stage, the committee will decide whether the patent will be granted or denied.

If the grant procedure is successfully completed, the patent is granted and the grant certificate issued. Over the nine months after granting, the patent may be opposed by third parties. Instead, at any time, the patent proprietor may request its limitation or revocation. In any case, decisions are open to appeal, and responsibility for decisions on appeals is taken by independent boards of appeal.

As far as costs are concerned, they vary considerably from one Country to another, and within the same Country, depending on many factors such as how patents are presented and the number of claims. The time it takes for a patent to be granted may also be different and generally ranges from 2 up to 5 years. Concerning the duration of patent protection, the current international standard establishes a term of protection of 20 years from the filing date, provided that renewal or maintenance fees are paid on time and no request for invalidity or revocation has been granted during this period.

1.5 Patent Law: patent rights defense

Patents have wide-ranging economic significance: they encourage further investment in research and development (R&D), and foster technical innovation, which is crucial to competitiveness and overall economic growth. In order to protect the interest of inventors and ensure that the ultimate goal of the system is met, all jurisdictions across the world have developed some limitations and restrictions to the exclusive right given by a patent. When a person or entity violates another person’s rights, he or she may be accused of “patent infringement”. As Durton points out, «such an infringement is legally frowned at and can result in a huge penalty or fine if the patent owner seeks for redress in court» (Durton, 2018, p. 31), irrespective of the infringement degree of intentionality. There are different kinds of infringement (e.g., direct, indirect, contributory, literal, etc.). Here again, each Country has its patent infringement laws that determine what is regarded as patented infringement.

In 1962, the Convention establishing the World Intellectual Property Organization was signed with the aim to create the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). WIPO formally entered into force in 1970 as one of the 15 specialized agencies of the United Nations, to encourage creative activity, to promote the protection of intellectual property throughout the world. Today, it consists of 192 member States and helps governments, businesses, and society realize the benefits of IP. However, it is difficult to discuss this topic on a global scale without dwelling too much on exceptions and singularities. There are no universally accepted patent laws as the rights conferred by a patent have time not only limits but also territorial limits. For this reason, in this dissertation, only European legislation will be taken into account, with particular reference to Italy and the United Kingdom.

1.5.1 European legislation

Besides having the possibility to apply for protection at the national or the international level, the applicant may also apply for protection at the European level. Hence, the existence of a European patent. The term “European patent” refers to a centralized filing and grant procedure under the EPC, signed in 1973. The purpose of this Convention is to recognize a single grant procedure valid for all Contracting States (Perotto, 2008, p. 30). Both Italy and the United Kingdom are currently members of the European Patent Organisation, together with other 36 Contracting States. The European Patent Office is headquartered in Munich, and English, French and German are the official languages. If the patent application is filed in a language other than the official languages of the EPO, its translation must be provided within two months for each Country designated in the application.

Since translation costs can be considerable, due to the intervention of specialized translators and the cost of filing each translated document, applicants should use market analyses to pinpoint the Countries for which they really need protection. It must be observed that this unitary procedure does not result in a single patent valid in all States, but a set of national patents. The cost of filing a European patent application varies according to the number of Countries chosen and includes filing and search fees, translation costs and application preparation costs. Nevertheless, applying for a European patent is a cost-effective and time-saving procedure, while maintaining the same legal effects. A European patent application can claim the priority of a national application or, as is less commonly the case, may itself be a first filing. The deposit procedure remains virtually unchanged. Once the novelty search has been carried out and the examination fee has been paid, the patent is accepted or denied (idibem, p. 31). Any case of infringement against a European patent shall fall under the jurisdiction of national law.

With the aim of making the existing European system simpler and less expensive for inventors, the Luxembourg Convention was signed in 1975. The aforementioned agreement intended to create a “unitary patent” which could enable a substantial reduction in patenting costs (in particular those relating to translation and filing), simplified protection of inventions throughout the European territory as the result of one single procedure, and the establishment of a single centralized system of litigation. According to Perotto (2008), this type of patent would have reduced translation costs by 50%. However, this Convention never entered into force due to a lack of sufficient ratifications by the Countries involved. The main reasons for its failure are the excessive cost of obtaining the patent and the mistrust of the power conferred by the Convention on the national courts of the Contracting States to decide on the possible patent invalidity throughout the European Community (Balice, 2019).

1.5.1.1 More in-depth: Italy and United Kingdom

In Italy, the administration of patenting, registration and granting of industrial property rights is managed by the Italian Patent and Trademark Office (in Italian, Ufficio Brevetti e Marchi, or UIBM), founded in 1992 and based in Rome. In the UK, the official government body responsible for intellectual property rights is the Intellectual Property Office (IPO), based in Newport, South East Wales. Over the years, the patent law of the Country has undergone several amendments, but «the current Patent Office of the UK was established on 1 October 1852 by Patents Law Amendment Act 1852» (Durton, 2018, p. 77).

Both Countries joined the EPC, but only the UK signed the London Agreement in 2008 (together with other 21 Countries), whose aim was to reduce translation costs incurred after the grant of a European patent. Under the London Agreement, the member States of the EPC are divided into two types:

- Countries having English, German or French as an official language: these Countries will no longer require a translation of the patent specification in order to validate the granted patent in that Country;

- Countries having a language other than those previously mentioned: these Countries will select one of those three languages and will only require a translation of the patent specification into the selected language (assuming the patent has not been granted in that language). They may require a translation of the claims of the patent into their national language.

The potential cost reduction varies depending on which Countries are selected for validation. Of course, cost reductions will be greatest where the validation Countries include those that signed up to the London Agreement.

Another difference between Italy and the United Kingdom lies in the definition of “patent”. In fact, for the United Kingdom, when reference is made to “patent”, it relates exclusively to the utility patent, while in Italy the term “brevetto” is used also in relation to the utility model patent, as well as the patent for new plant varieties.

As regards the time and cost of concession at the national level, in both cases it is a long and costly procedure, with minor differences between Italy and the United Kingdom. In Italy, on average, it takes between two and three years to obtain a patent, with an average filing cost, including fees and expenses and entrusted to a professional representative, of € 2,500.00- 2,700.00 (excluding VAT) (Università del Salento, 2012). Conversely, the whole process managed by IPO may cost about 4,000 GBP (including the patent attorney fee), and last about 5 years (Durton, 2018, p. 81).

It is important to remember that, the United Kingdom left the European Union on 31 January, 2020, and entered an 11-month transition period in order to implement new trading relationship and security co- operation. Therefore, as Durton correctly pointed out, «the practice of patent may be affected. There may be changes, especially for the UK inventors that prefer seeking a European Patent Convention» (Durton, 2018, p. 76).

1.6 Involved actors

The process of drafting, applying for, granting and protecting a patent is extremely complex and requires the intervention of various actors. Each of them has a specific role that should not be underestimated. It is possible to briefly identify the following main figures:

- the inventor (i.e., the applicant);

- the patent attorney or the patent agent;

- the patent office of competence;

- the translator or the translation company.

The inventor of the patent may be a single individual although, to an even-greater extent, he or she is represented by an organization, a company or a corporation coordinating and financing research aimed at developing the object of the patent. Inventors may be, for example, researchers in a laboratory or research center whose activity is financed by a company that, once the invention has been patented, will benefit from the right to exploit it. In fact, as Durton (2018, p. 92) points out, «just as with some other types of intellectual property, one can also transfer or give their patent rights to another person in an exchange for what a patentee considers as valuable, which in most cases is money».

However, it has repeatedly been said that the inventor should work in collaboration with an attorney in every step of the patent lifecycle to ensure that he or she is properly guided. Below is attorney Quinn’s remark (2014) on the matter:

For better or for worse, there is a popular misconception that patent attorneys and patent agents are not really necessary and an inventor can do it themselves and save money. The truth is that patent attorneys are among the most highly trained attorneys you will ever meet. In addition to having to successfully complete law school and taken a State Bar Examination, patent attorneys must have a scientific background or else they cannot even sit for the Patent Bar Examination. […] One reason you want to hire a patent attorney to help you, if you can afford one, is because it is extremely easy for inventors to make mistakes that will render their hopes and dreams of a patent null and void.

When the patent application is filed, the relevant national (e.g., UIMB, IPO, USPTO, etc.) or international (e.g., EPO, WIPO, etc.) patent offices come into play. For example, according to the EPO’s modus operandi for obtaining a European patent, the examination procedure is carried out by an Examining Division consisting of three examiners. In order to ensure maximum objectivity for the applicant, the entire Examination Division is responsible for the decision whether or not to grant the patent. Moreover, one of the three examiners oversees the patent, from its application to its granting or denial, and he or she will be responsible for any communication with the applicant, or his representative, on behalf of the division. Similarly, if opposition is raised, the Opposition Division, also composed of three examiners, will intervene.

Finally, it should be remembered that there is a need to entirely or partially translate the patent in most cases. For such a reason, one or more translators must also be included in the category of “actors involved”. The translator can an individual or, as in the case of my internship experience, a translation company. For sure, once a company is contracted, there will be several professionals involved in the translation phase: account manager, project manager, as well as a translator, to name but a few.

Read the next chapter “The language of patents“.