The role of CAT tools in Patent Translation

Tesi di laurea in Laboratorio CAT

Serena CUSCIANNA

UniversitĂ del Salento, A.A. 2018/2019

4. PATENT TRANSLATION

Perotto (2008, p. 15) defines the language of patents as a proper training ground for the translation professional. Patents relate to a single general inventive concept, which means that each patent deals with only one topic. For this reason, ideally, linguists should have a sectorial knowledge background about the patentâs domain. As Hartmann writes, «patent translation is not for the faint of heart or the disorganized. It demands a meticulous and rigorous approach to subject matter that may be complex and abstruse» (Hartmann, 2007, p. 16). A mistranslation may invalidate the patent, causing great financial damage to the inventor, possibly to the company for which the translator works and to the translatorâs reputation and career.

4.1 Differences between patent translation and general translation

The translation of a patent requires compliance with logics other than those normally observed, for example, for the translation of a narrative book. Patent translation, indeed, belongs to the category of technical and specialized translation. As such, a feature that certainly distinguishes it from general translation is the high degree of literality required (Cross, 2007).

Within translation theory, there are two polarized worlds: the trans- latere and the trans-creare (Katan, 2018). In the âlatereâ approach the translator focuses on the language of the source text to find the most appropriate phrasings to transfer what is communicated. Conversely, in the âcreareâ approach, the translator focuses on the meaning of the source text to create the most appropriate text for the reader to access what is communicated. The Roman poet Horace was the first to question the role of the translator and the concept of fidelity, marking the beginning of the dualism between word-for-word (literal) translation or sense-for-sense (free) translation (Katan, 2018). Thus, patent translation qualifies as a word-for- word, or source-oriented, translation. Cross (2007, p. 19) approaches this topic starting from the reaction that a translator might have when asked to translate a patent in a literal way:

For seasoned translators, literal translations are often objects of scorn. […] Many experienced translators are fond of saying that they translate meaning, not words. In most fields, the best translators are distinguished by their ability to make suitable word choices and to craft graceful sentences in the target language. They would shudder at the idea of slavishly reproducing the wording of the source text in a literal translation.

However, in patent translation, the target text must be perfectly faithful to the source text, reproducing all its original concepts. Syntactically, the source and target texts will have to be almost superimposable, limiting as much as possible the number of displacements of the sentence components. Therefore, it would seem to take a step backward in the evolution of translating theories. Indeed, patent translation, is at the antipodes of literary or editorial translation, in terms of the factors to consider in order to establish the quality of the text produced. Newmark (1988) defined translation as an attempt to replace a message and/or statement written in one language with the same statement and/or message in another language. Each translation involves a certain loss of meaning, oscillating between overtranslation (increase in detail) and undertranslation (increase in generalization). In the case of patent translation, it is clear that the loss of meaning must be kept to a minimum. Although one might think that a literal translation is impossible or even humiliating, «a better understanding of what is meant by the term literal in the context of patent translation, makes clear that the task is not only possible but […] actually requires significantly greater expertise as a translator» (Cross, 2007, p. 19).

If the translator leaves a word out of a list and it happens that that word has key importance in the invention disclosed in the patent, or if the translator chooses a word slightly different from the one used in the source language just to create a more fluid text, the invention runs the risk of being considered new when it is not, or to look likes what it is not. In this context, literal translation should not be confused with formal equivalence translation, which is opposed to functional equivalence. As Cross (2007, p. 22) points out, «functional equivalence means translating the meaning rather than the words, and it is fine for many types of translation», but not in patent translation. On the other hand, formal equivalence is obtained when «the translator reproduces both the words and the grammatical structures from the source text with as little modification as possible so as to recreate the form of the original» (Cross, 2007, p. 22).

A further challenge of patent translation is to maintain a one-to-one correspondence between SL and TL. Once the appropriate translation has been identified, the translator will not have to use synonyms. This is particularly applicable to nouns associated in the text with a reference number. For this reason, it is also crucial that an SL term is not translated with a TL term with another primary equivalent (Perotto, 2008, p. 58). During my personal experience with patent translation, it has often happened to find source texts in which two terms, normally considered synonyms, were used to refer to different elements, as in the case of âfaceâ and âsurfaceâ. In English, these two nouns are considered mutually synonymous and thus interchangeable in most cases. However, it often happened that they were used to refer to different components (with different reference numbers) of the same invention described in the patent. It also happened that two different terms used in the SL text had the same translation in the TL, as in the case of âdoorâ and âportâ. In Italian, in most cases, both terms are translated with “porta”, but, in the source text of a patent I had to translate, they were used to refer to two different elements. In such cases, the translator must carry out appropriate terminological research in that subject field to identify equivalents that would remain valid throughout the text without creating ambiguity or incorrectness. Thus, in the case of âdoorâ and âport, I translated them as âportaâ and âbocchettaâ respectively, while in the case of âsurfaceâ and âfaceâ, I translated them as âsuperficieâ and âfacciaâ respectively. Often, the only means to avoid ambiguity is to resort to a literal translation, even if sometimes it may produce a stilted target text. Concerning verbal use, it is interesting to underline the use of verbs such as ” comprehend”, “include”, “constitute”. The translation of such verbs is of considerable importance since in other contexts they could be considered almost synonymous, but in the patent field, they acquire different meanings. In this respect, please note the guidelines published on the EPO website in the “Guidelines for Examination” section on the use of the verbs “comprising” and “consisting of” in claims:

A claim directed to an apparatus/method/product “comprising” certain features is interpreted as meaning that it includes those features, but that it does not exclude the presence of other features, as long as they do not render the claim unworkable. On the other hand, if the wording “consist of” is used, then no further features are present in the apparatus/method/product apart from the ones following said wording.

In most forms of translation, as LevyÌ (2011, p. 55) states, «because the wording of a translation is derivative, an expression found in a translated work represents not the mandatory version but only one of a number of possible alternatives». On the other hand, the patent translator has little freedom to choose how to express the content of the original text.

Another critical situation in which the linguist must pay special attention is when the text of the patent contains errors: an incorrect chemical formula, a typographical error, an incorrect reference number, inconsistent terminology. In said cases, the translator should never alter the specification or include a translatorâs note, a footnote or an endnote. What the translator can do is to give the client a list of problems, or insert [sic] after the error. The law forbids the correction of errors as part of the translation process. For example, in the case of European patents to be translated into Italian for national filing, it is not allowed to file a translated version other than the already accepted European patent form filed with the EPO. Therefore, the translator is legally obliged to include in the translated version any errors the original EPO document may have (Perotto, 2008, p. 62). Conversely, in the field of general translation, errors are managed differently. Normally, the translator can contact the author of the original text in order to report the problem and ask for clarification, and agree to a modification.

4.2 The role of CAT tools in patent translation

Patent translation can be a challenging process. At the same time, its intrinsic characteristics and the strict rules imposed may represent an advantage that allows the translator to work faster and with greater confidence than with other types of text. CAT software is definitely an indispensable tool to guarantee the quality of the final product. With the use of a CAT tool the workflow can be streamlined if compared to process management without the use of said tools.

As mentioned in the previous chapter (see chap. 3.3.1), Trados offers the possibility to work with single files or projects. Working with projects is particularly useful when one expects to have to translate one or more files from a certain SL to multiple TLs. Creating a translation Project Package (i.e., zipped archives wrapping the translation resources need by the involved linguists and mangers) avoids repeating the required operations (e.g., adjusting settings, connecting TM, opening TB, etc.) on all the files contained in the project.

Another important help given in the translation of technical texts, such as patents, by most CAT tools available on the market, including Trados, is the possibility to merge TMs and TBs functionalities for terminology search into a single program. The presence of many technical terms demands close attention and good record keeping: both TMs and searchable TBs are effective for this purpose. The translator can choose if create a different TB by project, by client or by topic. TMs too play a key role in terminological research.

As stated by Hartmann (2007, p. 15), «in many patents, the same material appears more than once within specification; often there are parallels between certain portions of the specification and the claims». For example, the first paragraph of the specification is often identical to the preamble of the first claim; the abstract often mirrors the first claim; the disclosure of the solution to the problem is also the characterizing feature of the independent claim; and the details of the embodiment of the invention will form the characterizing feature of the dependent claims. Thus, the translator can take advantage of these echoes by using TMs, which can automate the process of finding and inserting these textual parallels with minimum or no changes.

Another unusual but possible case where the translator can benefit from working with a CAT tool is when acronyms are used in the text, especially with chemical or computer patents. Patent translators tend to keep in the target text the acronym as presented in the source text, bearing in mind that it is always advisable to break them down by presenting their meaning in the target language at the first occurrence (Perotto, 2008, p. 76). If the acronym is immediately recognizable and diffused also in the target language (e.g., SMS, CD-ROM, GPS, etc.), translators can avoid adding the explanation (Perotto, 2008, p. 76).

By using a CAT tool, the translator would be able to more easily identify acronyms in the text and speed up the translation process. For this purpose, the translator could identify the correct equivalent in the TL at the first occurrence and, subsequently, use the suggestions provided by the TM. Alternatively, he/she could save the SL and TL pair of the acronym as entries in a TB and then accept the translation provided during the translation process. Finally, if the chosen CAT tool offers this specific feature, he/she may use specific functions able to manage this type of textual elements. In Trados, in order to speed up the identification and insertion of acronyms, it is possible to take advantage of the “Placeables” function. âPlaceablesâ are SL contents that can be automatically localized in the TL and do not require translation. Acronyms fall into the category of “Variables”, a particular type of âPlaceablesâ. The user can create a customized list of variables associated with a TM, thus listing all the textual elements for which no translation is required and for which the corresponding SL content can be copied into the TL.

4.3 Short overview of MT and patent translation

Machine translation (MT) is an area of translation science that studies the automatic translation of texts from language A into language B using computer software. This new way of translating has played a leading role in the language and translation industry for several years now. Research in machine translation began in the mid-twentieth century and, although there have been some setbacks mainly due to a lack of physical resources to fund such studies (GarciÌa, 2014, p. 80), these tools are now powerful allies for a translator and, even more, for LSPs. Sophisticated and continually evolving MT can be accessed now on-demand through proper interfaces (i.e., remote procedures that can be activated from a client computer) or even from a Web browser.

The introduction of these new tools was not devoid of criticisms and skepticism. To understand how the opinion about and approach to machine translation have changed almost radically in recent times, it is sufficient to carry out a quick bibliographic research on the subject and take as an example some articles a few years apart. As Bennett and Gerber explains, «throughout its 50-year history, MT has been viewed as either a threat to translators or a boon to those who need translation; sometimes as both at once» (Bennett & Gerber, 2003). For example, Vitek (2000, pp. 2-7) had an extremely negative view of MT:

Unlike humans and chimpanzees, machines by definition don’t understand the meaning of anything and never will. This is why machine translation that aims at an accurate translation of the meaning of the original text is an exercise in futility. […] MT will never really amount to anything more than a tool, a useful tool for translating words from one language into another, words that do not necessarily say anything. […] To try to reduce human language, which is as complex as human thinking, to a series of zeroes and ones, is clearly an exercise in futility. […] If a translation done by a machine is accurate, it can be accurate only coincidentally because the machine does not understand the concept of accuracy.

While it is true that MT poses a threat to the human translator, it is also true that, today, the translation community is adopting a more practical, less reactive approach to the limitations and potential of MT. Besides, already in 1960, Bar-Hilal stated that MT had become «a multimilion dollar affair» (p. 91). Nevertheless, regardless of how much MT systems may be developed, they could never completely replace the human figure and exclude his intervention. Technologies are refined, but there are still clear limits and, as Riediger and Galati (2015, p. 1) point out, the question is no longer how technology can replace man, but what man can do to improve the performance of these systems. The MT market indeed is in constant growth and is set to transform many translators into post-editors as well. As GarciÌa explains, «post-editing, the manual âcleaning upâ of raw MT output, once as marginal as MT itself, has gradually developed its own principles, procedures, training, and practitioners» (GarciÌa, 2014, p. 81).

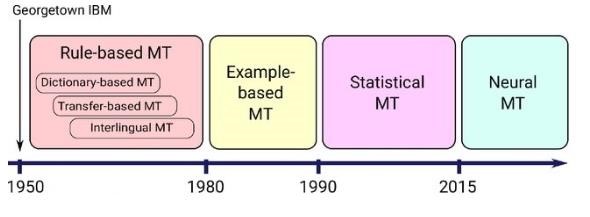

Although it is often thought to be a unique form of translation, MT is a macro category that encompasses several typologies (FIG. 7). Overtime, different approaches have been defined and have gained maturity for practical use today (Sepesy MaucÌec & Donaj, 2019):

- Statistical Machine Translation (SMT): it uses statistical parameters derived from the analysis of a large number of monolingual or bilingual corpora in order to reach the best sentence structure, and the best translation. Rather than grammatical rules, the probability of occurrence and frequency of words are taken into account. The quality of the output obtained with this type of system is strictly related to the quality and volume of the used corpora. «There is growing emphasis on SMT. […] If source texts are written consistently […] outputs can be significantly improved again» (GarciÌa, 2014, pp. 80-81);

- Neural Machine Translation (NMT): it uses machine learning technology to teach software on how to produce the best result. Neural networks take into account elements such as gender, language register, word type, etc., connecting them within a specific context, to allow the computer to offer optimal output.

Timeline of MT evolution (Source: (Sepesy MaucÌec & Donaj, 2019, p. 3))

The first attempts to integrate MT into CAT occurred in the 1990s with poor results. Lingotek, a cloud-based translation services provider, was the first to launch a Web-based CAT integrated with a mainframe powered MT in 2006. SDL Trados soon followed suit (GarciÌa, 2014, pp. 80-81). Nowadays, many translators and translation agencies, such as Global Voices, use the outputs generated by MTs as the starting point of the CAT process. Having an MT integrated into the chosen CAT tool allows translators to continue working in a familiar environment and use their TMs and TBs, thus keeping the option of editing suggestions if deemed useful enough, or discarding them and translating them from scratch. Nevertheless, on the actual benefits of using this system, GarciÌa (2014, p. 81) seems uncertain:

While the process may seem straightforward, the desired gains in time and quality are not. As noted before, fixing fuzzy matches below a certain threshold (usually 70 percent) is not viable; similarly, MT solutions should at least be of gisting quality to be anything other than a hindrance. This places translation managers at a decisional crossroad: trial and error is wasteful, so how does one predict the suitability of a text before MT processing? Unfortunately, while the utility of MT and post-editing for a given task clearly depends on the engineâs raw output quality, as yet there is no clear way of quantifying it.

According to Bennett, & Gerber (2003, p. 186), a major role is played by the type of text: «over 50 years of MT research have made it clear that not all texts are translatable with MT at an acceptable level» (Bennett & Gerber, 2003, p. 186). Literary or theatrical texts are the least suited for MT. Their structure is complex, and the text often requires a genuine interpretation by the translator to reproduce exactly the meaning and style. In short, there is far too much extra-linguistic content. On the other hand, technical documentation (e.g., patents), help files, and professional publications are more eligible. With these kinds of texts, «the results are quite good, as much as a 50% productivity gain over pure human translation» (Bennett & Gerber, 2003, p. 186). It is noteworthy that, in a few years, there has been a clear change in general opinion about MT, as a result of the rapid development in IT. Only three years earlier, Vitek (2000, p. 3) had made a sharp comment about MT in patents:

Most of the time, the machine product will be crude and almost incomprehensible, even if it’s a very simple descriptive passage. In my opinion, forcing patent lawyers to go through this process every time when they need to arrive at the real meaning of a sentence represents abuse of very intelligent humans by dumb machines. I would also argue that not even patent lawyers are paid enough to deserve being abused by unfeeling machines in this manner.

In conclusion, it is clear from what has been said so far that the translators have not chosen a common line about MT. However, as a result of personal patent translation experience, it is impossible not to recognize the massive contribution made by MT when translating a patent. Time and deadlines are often tight and one does not always have specialist knowledge in the subject field of patent, so it is vital to minimize the time spent on translation. The importance of MT to the patent system has also been confirmed by the study conducted by Larroyed (2018). «The results proved that, although improvements in patent machine translation are still necessary, most of the content of the patent is disclosed through it, with the average disclosure being almost 80%» (Larroyed, 2018). Human involvement is still fundamental in choosing the correct technical term, or in organizing the syntax. Nevertheless, «these challenges do not diminish the significance of the quality of machine translation reached until now. Although machine translation can still improve, it clearly discloses patent information and represents one of the main bases of communication within the patent system» (Larroyed, 2018). Besides, despite the prejudices, MT also makes it possible to overcome language barriers that were once insurmountable in the disclosure of patent information. Further confirmation that using MT in the patent field is not a totally wrong strategy comes directly from WIPO. Taking advantage of NMT, WIPO developed a translation software. It was originally limited to patent translation, but, today, it is possible to choose a specific technical domain in order to benefit from this tool also with other types of texts. However, WIPO is not the only entity to offer MT tools. For example, EPO works in partnership with Googleâs NMT technology, and offers the possibility to translate in several languages the results of prior art researches.

4.3.1 DeepL

Nowadays, it is possible to collaborate with increasingly refined and reliable MT systems, such as DeepL (i.e., the machine translation service launched in August 2017, see https://www.deepl.com/home). As can be read in a relatively recent article in the Italian daily newspaper âLa Repubblicaâ, DeepL is an NMT system that uses a high-powered computer able to translate a million words in less than a second. The DeepL team uses this supercomputer to train neural translation networks on a vast collection of multilingual texts. During training, the networks examine a multitude of translations and learn to translate independently, with correct grammar and wording. To this end, DeepL can rely on the success of its first product: Linguee (https://www.linguee.com/), the world’s largest translation search engine. Over the last decade, DeepL has collected over a billion high-quality translated texts, collecting the best possible training material for a neural translation network.

Over the past three years, many scholars have already conducted researches in order to support or disprove the common idea that DeepL is better than other known systems in terms of translation quality. For example, according to Volkart, Bouillon, & Girletti (2018, pp. 148-149), «the output produced by DeepL was faster to post-edit and required fewer corrections», with an overall idea that «the final translation tends to be of better quality» if compared to a customized Statistical MT system. Of the same opinion are Macketanz, Burchardt, & Uszkoreit (2018, p. 7) who confirm that «DeepL performs a little better than Google […] and by and large produces a more natural and fluent output».

As with CAT tools, there is no âbestâ MT system. However, in the last two years, the MT scenario has significantly evolved, as shown by Savenkov (2019) report. He takes into account a variety of MT systems, but DeepL has proven to be valid in multiple language combinations and application domains. Although the number of language pairs supported by DeepL is much lower than that of other competitors such as Google (72 – DeepL vs. 10506 – Google), DeepL is within 5% of the best available MT Quality for a language pair (Savenkov, 2019).

Although DeepL is not the only application that can deliver a satisfactory MT result, Chapter 5 of this dissertation will be limited to analyzing the outputs produced by DeepL since it is a tool actually used by the translation company where the internship was carried out.

Read the next chapter “Analysis of the translation of patent with CAT tool“.