My name is Barbara Bulf, I graduated a year ago from the Master’s degree in Languages for communication in international enterprises and organizations of Modena and Reggio Emilia. I am passionate about a few things, including cinema, music and translation, and I often wonder about social issues. Today I would like to focus on this date for a bigger topic: the gender pay gap. But let’s take it step by step.

Everybody knows, more or less, what March 8th celebrates: in the collective memory, we are reminded of the numerous mimosas and gifts dressed with affectionate wishes for the female figures that surround us. Even in 2022 we are celebrating our mothers, sisters, wives, grandmothers, aunts, cousins, girlfriends, daughters and friends. We celebrate women, but it would be better to celebrate International Women’s Rights Day to bring attention back to rights and equality.

So why do we celebrate the 8th of March?

The date relates to a demonstration that took place in 1917 in St. Petersburg, Russia, where many women gathered in the streets to demand an end to the war. It was the first of a series of protests that led to the collapse of Tsarism. Later, in 1921, during the Second International Conference of Communist Women held in Moscow, it was decided to designate March 8 as International Workers’ Day, which would later become the more famous Women’s Day.

It can not be more current than that, then, this March 8: a holiday born from a Russian demonstration against the war. But it is not the Russia-Ukraine conflict that I want to talk about today, although I believe it is important to demonstrate for the rights of all, and especially for the right to peace.

On International Women’s Rights Day, I would like to reflect on the gender wage gap, which has always, and particularly since the beginning of the pandemic, affected not only women, but all of society.

In 2020, women suffered more penalties in earnings because they were more likely to be employed in sectors such as education and administration or in caregiving where they were highly likely to be suspended, fired, or forced to work part-time.

They typically do unpaid care work – more than men – and this responsibility increased after the pandemic because of the closure of schools, disability centers, and increased needs of elderly relatives. More women than men lost their jobs, and the wage gap was often brought up.

The interest that led to the creation of this paper therefore arose from the curiosity of the term since the phenomenon itself – gender pay gap – is not easily measured nor easily resolved. I have therefore investigated the methods found to measure the pay gap, I have traced the laws that have attempted to address the problem and I have delved into the reasons drawn up by the European Commission, noting that discrimination, although prohibited, continues to contribute to the gender pay gap.

Finally, I brought into analysis two methodologies that attempt to address the Pay Gap caused by discrimination, the Icelandic and Swiss models. The analyses showed that the Gender Pay Gap problem is the result of a series of actions not necessarily related to deliberate discrimination, although sometimes it is, but to different circumstances that in the extreme end up disadvantaging women relative to men.

The Gender Pay Gap is a phenomenon that still exists but has seen a gradual decline over the decades. It’s mostly calculated as the Unadjusted GPG, defined as the difference between the average gross hourly earnings of men and women expressed as a percentage of the average gross hourly earnings of men.

In 2019 in Europe, in terms of pay between genders there was a gap of 14% according to Eurostat. Having said that, we need to take into account that there are many elements that influence the amount of salary such as, for example, the type of work, the number of hours worked, etc. so as the name implies, the unadjusted GPG can be potentially misleading because only the average wage is considered, which could lead to the assumption that the gap is only due to discrimination.

We need the adjusted GPG, which is obtained when variables such as hours worked, occupations chosen, education, job experience, and geography are considered. By accounting for these variables we can more accurately quantify workplace pay discrimination against women.

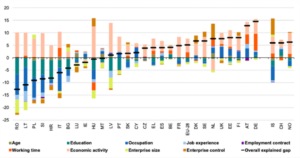

DECOMPOSITION OF THE EXPLAINED GPG, 2014 – SOURCE: EUROSTAT

Now, this is a graph that takes into account only the explained part. In the transition between unadjusted and adjusted these 9 factors are taken into account: age, working time, education, economic activity, occupation, enterprise size, job experience and employment contract, thus getting the overall explained gap that explains part of the UNADJUSTED GPG: here positive and negative factors emerge.

Those above the zero level will have a directly proportional effect on the GPG, so the larger they are, the greater the gap. While below zero they will have an inversely proportional relationship, so the larger they are the lower the gap should be. Some factors that are positive in one country may be negative in another due to the sociocultural context. Interestingly, in the EU, the negative gap recorded for education is -1.2%, meaning that women should earn 1.2% more than men because of the higher average level of education. Same thing for Italy, where women have higher education but are paid less overall. The problem is economic activity, because women on average work in occupations that pay less.

The European Commission has prepared a specific study on the situation of gender equality which includes equal pay. In fact, in the section Justice and Fundamental Rights of its citizens, four main reasons for the existence of the gender pay gap are named: first of all, sectoral segregation: this means that women are over-represented in occupations that pay less while men are over-represented in jobs that give higher salaries. This segregation is often due to the belief that women – whether they are aware of it or not, willingly or unwillingly – choose jobs that are more in line with the female stereotype, characterized by low pay and poor career prospects, but more compatible with managing family responsibilities. Girls tend to choose less the scientific studies, which are more than before needed in the labor market.

The second reason relates to work-life balance where women perform, much more than men, unpaid care work and this affects not only their hourly wages, but also has a negative impact on career opportunities and retirement.

The third reason has to do with the glass ceiling: the position in the hierarchy influences the level of remuneration and, the European Commission noted that less than 10% of CEOs of top companies are women. It’s a female disadvantage in promotion where women struggle to reach higher work positions than men.

The last part of the big chunk of the problem is discrimination, where in some cases, women earn less than men for doing jobs of equal value. The gender pay gap is also reinforced by beliefs that women are inferior to men and cannot produce work of equal caliber to their male counterparts.

There have been many laws, directives and treaties promoted by the Union, which have supported women’s rights, both in terms of equal participation in the labor market, and in terms of the gender pay gap and thus combating discrimination. The Treaty of Rome included the principle of equal pay for equal work. With the entry into force of the Treaty of Amsterdam in 1999, the promotion of equality between men and women became an integral part of the Union’s Charter of Fundamental Rights, prohibiting discrimination on any ground, including sex, and recognizes the right to gender equality in all areas and the need for positive action to promote it.

Iceland was in 2018 the first country to introduce legislation that requires companies to certify equal pay against discrimination. This legislation is based on a tool called the Icelandic Equal Pay Standard, which aims to eliminate the gender-adjusted wage gap. The standard applies to all companies and institutions with more than 25 full-time employees. Employers will have to look at each position, decide what duties it implies and then assign a value to the position, which means that salaries will be determined based on the role and not the person. This certificate must be renewed every three years. By not meeting the standards and therefore not receiving the certification, employers will face fines.

Another example of action focusing on gender wage equality was launched in Switzerland with the EQUAL-SALARY Certification. The non-profit foundation Equal-salary was launched in 2010 by Véronique Goy Veenhuys and developed in collaboration with the University of Geneva. The Foundation is committed to accrediting companies that pay women and men equally for the same work. Audits are entrusted to partners such as PwC and the Swiss Confederation has financially supported the development of the certification, which has also been recognized by the European Commission since 2010.

The company uploads the employees’ data on the EQUAL-SALARY Foundation’s protected IT platform. All data are pseudonymized before being analyzed by PwC and destroyed at the end of the procedure. A statistical regression model is used to analyze the difference in equal pay for equal work between men and women. To proceed to Step 2, the difference must be ≤5% and the regression coefficient ≥90%.

A list of individual employees who are underpaid is provided so that the company can prepare a remediation plan. PwC conducts a visit to the company to assess management’s commitment to equal treatment of men and women, and to assess employees’ perceptions of equal treatment. Depending on the result of the visit, the Foundation awards the EQUAL-SALARY certificate.

This gives the right to use the label on all company communications, such as the website, recruitment ads, letterhead and annual reports. The certification is valid for three years, and during this period, the certified company undergoes two follow-up visits to demonstrate its commitment to policies of fair and non-discriminatory treatment for men and women.

Why is it important that there is no wage discrimination based on gender or skin color or any other discrimination? According to the Equal Salary Foundation, not only because it’s purely and simply fair to pay employees the same amount for equal work, but it’s also good for the company’s own business.

In fact, the path to certification leads to numerous benefits: it establishes a culture of trust and transparency, increases employee loyalty and attracts a new generation of talents and demonstrates to customers and competitors that the company with the certification stands for fairness and progress. It’s a win-win approach for demonstrating a commitment to equality to its employees and donors.

There are 3 companies in Italy that have applied for and obtained this qualification and they come from very different sectors. The first is the multinational Philip Morris, a U.S. company active in the tobacco industry, which in 2019 brought all its sites, including the Italian one, to be certified. The second to undertake the audit for certification is Ferrari S.p.A. certified in 2020, which is known to operate in the automotive industry, traditionally considered a male-dominated sector. The last Italian company to be certified is a bank, Gruppo Credito Emiliano. All three companies, although coming from different sectors, have in common the fact that they are based in Emilia Romagna.

In conclusion, there is no doubt that a pay gap exists, but the causes are multiple and culturally rooted. In order to reduce the Gap, I believe that first of all, the participation of women in the labor market must be encouraged and supported with greater strength, including motivating the younger generation of girls to undertake courses of study in disciplines that the labor market requires more than before. It would also be necessary to push for continuous training even during the course of employment, encouraging those structures that can replace employees in family care duties.

There should be a fair distribution of parental leave between men and women and thus increase women’s participation in the labor market. Women should have a real choice about how to combine work and family life also to break gender stereotypes.

A third approach should be aimed at encouraging greater transparency in companies and to do this, the state (from a normative point of view) should push companies to obtain a certification of equal pay. Promoting transparency could help achieve gender balance within management and gradually lead to a more balanced system throughout the entire society.

The Author’s LinkedIn Profile, here.